“LeBron James has missed the most shots in the NBA. But he’s also scored the most points. So, if we never shoot, we never score. The same applies to AI: don’t be afraid to try and make mistakes. Today, the public sector is afraid of making mistakes; it is being governed by a faulty national system that doesn’t motivate employees to strive for more and only threatens them not to make mistakes. As a result, the pace of AI integration is rather slow,” says Vytautas Šilinskas, former Minister of Social Security and Labour and AI enthusiast, when asked about the situation regarding the application of AI in the Lithuanian public sector.

Giedrius Karauskas, Head of the Technology Division in the language technology company Tilde in Lithuania, spoke to him about why we are not the forerunners of the EU digital transformation, what the biggest failures of the public sector are, and what is being discussed regarding AI in the closed circles of EU politics.

GIEDRIUS KARAUSKAS, Tilde: According to the Government AI Readiness Index 2024, Lithuania ranks 35th among 188 countries regarding its readiness to integrate artificial intelligence (AI) into the provision of public services. And although we can see a breakthrough, we are still not the forerunners. What is holding us back, in your opinion?

VYTAUTAS ŠILINSKAS: In the public sector, the main problem is ageing and unmotivated management. After regaining national independence, businesses reformed quickly and adapted to Western culture, as otherwise, they simply would not have survived, while the principles of public sector management remained unchanged. And they’re very simple: taking risks and trying to innovate in business is worth it because if you’re successful, you’ll earn a bonus, and if you’re not – it’s ok. People are not afraid of making mistakes. In public institutions, people are afraid of making mistakes because their management is based on the principles of enforcement, control and responsibility, where responsibility means answering for the mistakes you make. There’s no motivation and encouragement for doing a good deed – you’re only punished for your mistakes. And when you’re only motivated by punishment and negative incentives, you choose the safest way. This issue is not exclusive to Lithuania; it exists in other countries as well. The public sector chooses tried and trusted means that work elsewhere. During my term of office, I tried to change this in order to create a sense of security for people so that they’d know that they wouldn’t be punished for their mistakes but would be rewarded for extra effort. Choosing the safest way for innovation creates an impenetrable block: innovation in itself means risk, and there is no motivation for risk-taking in the public sector; there is only a fear of making mistakes. So, if we want to implement a serious digital transformation, we need to fundamentally change the governance model and culture of the public sector, encourage people to do more and motivate them without the fear of punishment and threats about making mistakes.

GIEDRIUS: Many still fear that AI will take their jobs. For instance, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates that the breakthrough of AI and related technologies may affect up to 25% of the world labour market. What is your opinion on this? What have you heard from government officials and executives?

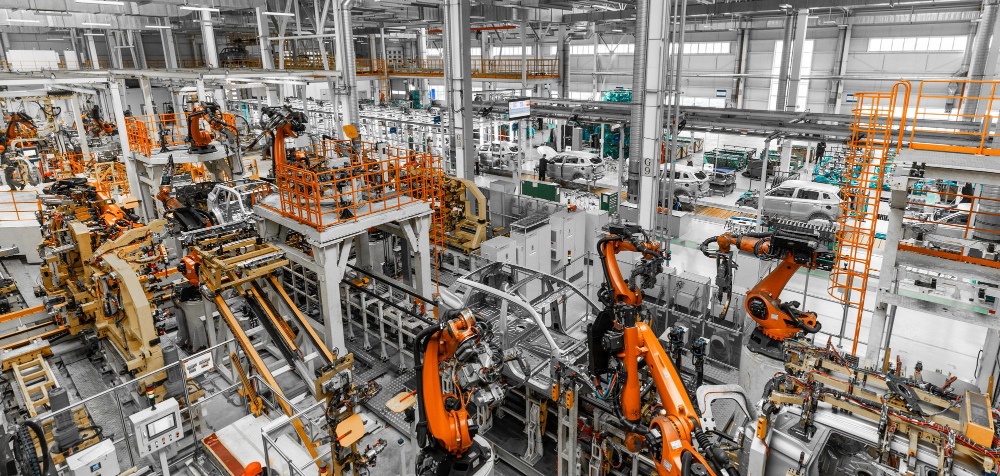

VYTAUTAS: Well, first of all, in order to accelerate innovation and the development of tools, it should be communicated that this is not a solution to replace humans but rather a tool to help them. If a manager says we’ll implement AI and then fire half of the team, he or she will never gain their support, but if a manager says we’ll implement AI to reduce the share of tedious and monotonous work and keep the salaries unchanged, he or she can gain immense support. Secondly, there is no need to fear that certain jobs will disappear. Remember the recent history of Lithuania: when we restored independence we had over 20% of people working in agriculture. It now employs around 5%. So, how many jobs were lost in agriculture? A lot, but it’s not bad, and nobody misses them. On the contrary, it is progress. Today, these people are doing other easier and nicer jobs. The decline of such jobs is, on the contrary, the goal, and we really still have some room for improvement, as, for instance, merely 1% of the workforce is employed in agriculture in the US, and 2–3% per cent in France. Today, our biggest employer is the industrial sector, where we really have room for improvement in terms of efficiency and productivity, which can easily be done with AI and automated solutions. Looking to the future, if we manage to reduce the number of tasks but retain or increase our productivity, we will simply need to work less. We can spend more time with ourselves, family and friends. This must be actively pursued.

GIEDRIUS: What is the European approach to the issue of job losses due to AI? Do such fears exist there, too?

VYTAUTAS: Three years ago, almost all social security and labour ministers in the European Council only talked about AI in terms of risks, not opportunities. The general train of thought was that AI had to be fair to everyone, that AI couldn’t rob people of their jobs, and that we couldn’t take risks. So, then I tried to talk to them on their terms and told them that if we took the risk and failed to integrate AI, we would fall behind, and those jobs would disappear altogether and not be replaced by alternatives. For example, if we do not implement AI and increase productivity through automated solutions, the automotive industry will no longer exist in Europe but will soon be taken over by the Chinese, who will be able to produce their cars faster, cheaper and more efficiently. If we don’t innovate, they will. But the situation has changed. At another meeting last year, the ideas were quite different, and ministers have already said that we need to innovate and that we need to help businesses transform faster. So in just one term of office, four years, the general consensus not to make rushed decisions has changed to acting swiftly. This is not so apparent in the public, but in private discussions between politicians, AI adoption is a very important topic.

GIEDRIUS: There is also a great deal of debate about the EU AI Act, and it’s said that it will reduce our ability to integrate quickly and make full use of AI’s potential to increase Lithuania’s productivity and progress as a state. This is particularly evident when comparing Europe with the US, where businesses are allowed to experiment much more with innovation. What do you think about this regulation?

VYTAUTAS: Well, there’s an anecdote that is quite true in its essence: while the US is innovating, Europe is regulating. This is a real problem, and it grew worse when the United Kingdom left the EU, which was a sort of counterweight, as it always advocated for less regulation. The EU and the US have two very different legal traditions: Anglo-Saxon and ours, German. The US acts first and then repairs the flaws, while we create regulations first and try to do it safely before we do it. The way to innovate in the US is, therefore, much simpler and less burdensome. We provide lawyers with an assessment of how to use and implement innovations, and although I am a lawyer myself, I know that they do so without fully understanding the technologies themselves. Both in Lithuania and in Europe, too much power is given to lawyers: the lawyer’s word is sacred. But this is not the case; it is business that decides, and it is society that decides. Politicians who work in this context know more than just documents or legal provisions – they also know the context. Moreover, public sector lawyers maintain the position that if something is not written, it means that it is prohibited. In the private sector, we have quite the opposite rule: if it’s not written, it means that it’s allowed. I have explained this distinction on several occasions to the public sector lawyers, but it is precisely because of this that it’s difficult to make the communication work, and the processes are not moving as quickly as they could.

GIEDRIUS: All right, let’s talk about data as the main argument for implementing AI. It is already being discussed around the world that data has been exhausted and that everything has already been sucked up, but it seems to me that we still have some data in Lithuania that’s being stored in the wrong places. Although the data is provided, the process is slow and sometimes inefficient when using data for AI solutions. Do you think it’s realistic to have at least 90% open data in Lithuania that would help integrate AI into processes and make both business and public organisations more efficient?

VYTAUTAS: It is realistic, but it’s uncertain how soon it will be done. There is a lot of internal resistance, and there are many unfounded fears about GDPR; I have fought a lot against this myself during my term of office. Here, again, we are faced with the weakness of public sector management: people are not encouraged to do more and are afraid of making mistakes. They are afraid of GDPR, so they stop immediately when they see anything about data because it can lead to errors and severe liability. But this is changing slowly, and we have very good examples: The State Data Agency is trying to persuade other institutions to transfer data to our so-called data lakes; it has very strong analysts, creates its own incentives, and offers help, which is unheard of in the public sector. Of course, there is still an entrenched desire to take a safer path; a fair amount of lawyers do not allow data to be used in practice, but the breakthrough has been very serious during this term of office. I believe that there will be continuity because there is strong leadership and a good organisational culture.

GIEDRIUS: The State Data Agency really works well and has a strong technological base that allows for the faster, more efficient and cheaper development of new solutions when one service is built on another. What other good examples do we have, is there something that we don’t notice?

VYTAUTAS: I am impressed by the decision of the Employment Service, where AI is used to assess people’s employment capabilities. AI sorts the applicants according to those who need more attention from specialists and those who are hardly in need because they are highly qualified, thus reducing the workload for service providers. And this workload is actually immense – a single service provider has several hundred jobseekers. A good example is the Labour Inspection: it automates the collection of data from public sources by analysing potentially illegal work and assessing the risks. Well, it’s evident that chatbots are being deployed by an increasing number of public authorities working directly with customers: here, AI helps to serve more customers more efficiently, and the results are really very good. It allows people to get advice at their convenience, for example, after working hours or at the weekend.